Don’t Fear Change

by Stacy Rinella | March 20, 2024 7:00 am

[1]

[1]In 2023, the hottest year on record, extreme temperatures were experienced even in traditionally temperate locations, with deadly heat domes lingering for weeks over large swaths of the Northern Hemisphere. This is a preview of things to come as the effects of climate change materialize. This trend will result in increased air conditioning usage in regions that are already hot, as well as the necessity to install air conditioning in temperate regions that have traditionally operated without it. Overall, this will lead to higher energy consumption and associated greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from both energy production and refrigerant use, representing a concerning positive feedback loop. The International Energy Administration (IEA) estimates cooling demand will increase by approximately 150 percent by 2050 (300 to 600 percent in developing countries). High afternoon temperatures also exacerbate the existing limitation of solar energy reliance with peak solar production tailing off as late afternoon peak energy demand increases.

[2]

[2]that are solid at lower

temperatures and change to a liquid or gel at higher temperatures, absorbing a

significant amount of latent heat in the phase change.

Part of the solution to this problem is increasing the air tightness and insulation in building enclosures, but there are limitations to executing this in existing buildings. Deploying batteries to store energy is also an effective strategy and it is becoming more viable as costs plummet and technology improves, but again, there are limitations due to availability of mineral resources for battery manufacturing and the rapidly growing demand in the electric vehicle market that will take precedent over applications for buildings.

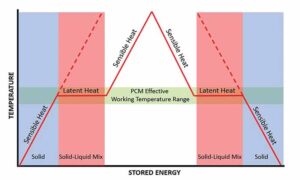

One promising technology that deserves a fresh look is building integrated phase change materials (PCMs). PCMs are materials that are solid at lower temperatures and change to a liquid or gel at higher temperatures, absorbing a significant amount of latent heat in the phase change. As ambient temperatures drop, they release the stored heat as they solidify and “recharge” to be ready for another warming cycle the next day. PCMs serve a similar function to thermal mass in a building, creating a lag in indoor temperature change relative to outdoor temperatures to delay indoor temperature peaks, but are lighter weight, less space intensive, and have lower embodied carbon.

By acting as a thermal battery (storing and releasing latent heat), PCMs can offset demands for space heating and cooling and thus dependence on air conditioning, improving occupant comfort while saving energy and cutting GHG emissions. A National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) study indicates that PCMs integrated in a building enclosure could reduce heating and cooling demand by 25 percent. Other studies of PCMs within the building envelope show a potential peak temperature reduction of 4 to 6.6 C (7 to 12 F).

PCMs fall into three classifications: organic, inorganic, and eutectic. The first attempts at integration of PCMs into building materials used organic phase change materials like paraffin wax or fatty acids, typically encapsulated in plastic to prevent leakage when in liquid form. Today, much of the promising research and product development is focused on inorganic PCMs like salt hydrates, and eutectics, such as sodium chloride and water. These tend to provide higher performance, greater flexibility in form, lower weight, and less concern with flammability.

The primary applications for building-integrated PCMs include interior wall boards and ceiling panels, sheet products integrated with or adjacent to insulation in wall cavities, immersion in porous masonry materials, or as part of an exterior wall or roof enclosure system. Other applications include PCMs integrated with HVAC systems for heat recovery, and for cooling of electronic equipment (servers, etc.). Researchers at Texas A&M are experimenting with 3D printable PCMs that could be easily applied to conventional building materials.

There are three main parameters that need to be considered to optimize the thermal performance of building-integrated PCMs:

- Melting temperature—The temperature at which a phase change occurs in the material must match the anticipated design conditions where it will be placed. A project in Phoenix probably requires a different PCM formulation compared to a project in Seattle.

- Thickness/quantity—The amount of the PCM will determine how much heat it can absorb. This must be optimized with the design criteria to provide sufficient thermal storage capacity.

- Position—The positioning of the PCM relative to the occupied, climate-conditioned environment will influence its effectiveness. Generally, the PCM should be on the hot side of the building enclosure, meaning exposed to the outside ambient conditions in hotter, cooling-dominated climates, and near indoor conditioned spaces in colder, heating-dominated climates. However, some applications within wall assemblies have been shown to work in both heating and cooling conditions.

Commercially available building products with integrated PCMs are currently limited, and there are still barriers to market viability. However, research and development are ongoing, leading to the anticipation of new products in the not-too-distant future. A PCM solution integrated with a thin, lightweight cladding system, suitable for new construction and retrofit applications, would be a particularly welcome innovation. There are numerous existing multi-family residential buildings without air conditioning that need a feasible and effective retrofit solution to achieve greater thermal resilience in a warming climate.

A combination of complementary solutions is needed to keep people safe and comfortable indoors as the planet warms, without increasing the use of air conditioning with its associated energy costs and greenhouse gas emissions. Building integrated phase change materials could play a significant role alongside high-performance building enclosures and renewable energy systems in making buildings healthier, thermally resilient, and climate friendly.

Alan Scott, FAIA, LEED Fellow, LEED AP BD+C, O+M, WELL AP, CEM, is an architect and consultant with more than 35 years of experience in sustainable building design. He is director of sustainability with Intertek Building Science Solutions in Portland, Ore. To learn more, follow Alan on LinkedIn at www.linkedin.com/in/alanscottfaia/.

- [Image]: https://www.metalarchitecture.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Alan-Scott_headshot_2024_cropped-1.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.metalarchitecture.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Phase-Change-Material-graphic-1.jpg

Source URL: https://www.metalarchitecture.com/articles/columns/dont-fear-change/